Behavioral finance is essential because it provides a deeper understanding of the psychological factors that influence financial decision-making, often leading to irrational actions in markets. Traditional financial theories assume that investors are rational, yet behavioral finance reveals that emotions like fear, greed, and biases such as overconfidence or herd mentality frequently impact choices. This insight helps financial professionals anticipate and interpret market anomalies—such as bubbles or sudden sell-offs—that standard models can’t fully explain. For investors, understanding these behavioral patterns can lead to better, more conscious decision-making, helping them avoid common pitfalls and improving financial outcomes. By recognizing and addressing biases, behavioral finance enables a more balanced approach to managing risks and achieving sustainable growth in personal and institutional finances.

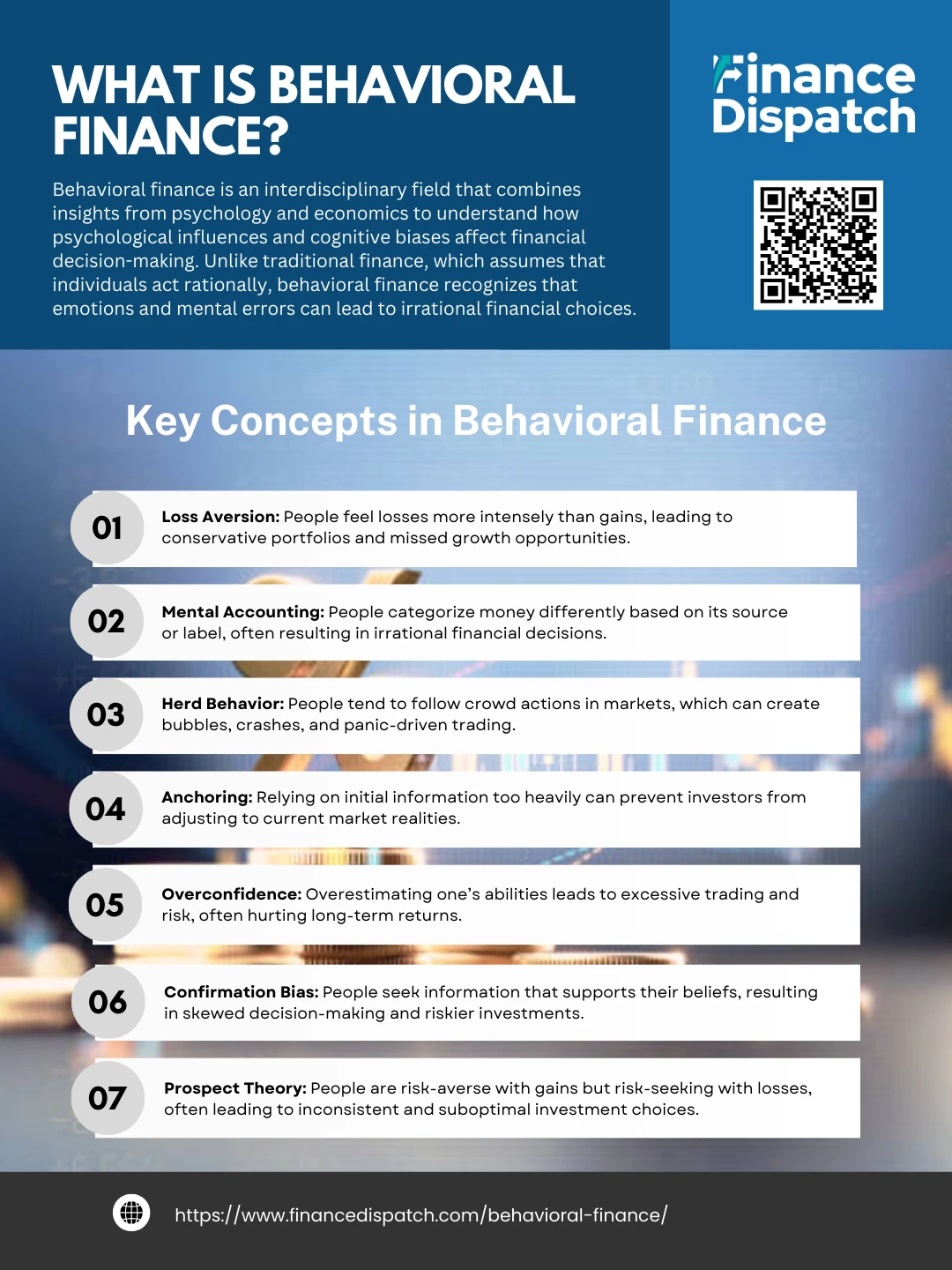

Key Concepts in Behavioral Finance

Behavioral finance is built on several key concepts that explain the psychological influences driving financial decision-making. By understanding these concepts, investors and financial professionals can recognize patterns of behavior that often lead to suboptimal choices and market anomalies. Here are some of the main concepts in behavioral finance:

1. Loss Aversion

Loss aversion is the tendency for individuals to prefer avoiding losses over acquiring equivalent gains, a behavior that can significantly impact financial choices. Studies show that people feel the pain of a loss about twice as strongly as the pleasure of a gain of the same amount. In practice, this leads investors to hold on to underperforming stocks longer than is rational, hoping they’ll “get back to even,” rather than selling at a loss. Loss aversion can result in overly conservative portfolios, where potential for growth is sacrificed to avoid any possibility of loss, often resulting in underperformance compared to market benchmarks.

2. Mental Accounting

Mental accounting refers to the way people categorize and treat money differently based on its source, purpose, or how it is labeled in their minds. For instance, someone may treat a bonus or tax refund as “extra” money and spend it more freely, even if it would be wiser to save or invest it. This mental separation can lead to irrational financial behaviors, such as carrying high-interest debt while maintaining savings in low-interest accounts. Recognizing this tendency helps individuals apply a more uniform approach to their finances, improving consistency in saving and investing decisions.

3. Herd Behavior

Herd behavior is the tendency to mimic the actions of a large group, even if those actions run counter to one’s initial judgment or rational analysis. In financial markets, herd behavior often leads to the rapid rise and fall of asset prices, creating bubbles and crashes. During a bull market, for instance, investors may rush to buy overvalued stocks because “everyone else is doing it,” only to suffer losses when the bubble bursts. Conversely, herd behavior can lead to panic selling during market downturns. Understanding herd behavior allows investors to evaluate trends critically, helping them make independent decisions rather than blindly following the crowd.

4. Anchoring

Anchoring is a cognitive bias where individuals rely too heavily on the first piece of information they encounter when making decisions. For example, if an investor buys a stock at $100 and the price falls to $80, they may anchor on the initial $100 price, refusing to sell until the stock recovers, regardless of the stock’s current fundamentals. Anchoring can cause investors to overlook changing market conditions or ignore signs of overvaluation, leading to poor investment choices. Recognizing this bias can help investors make decisions based on present market data, rather than on irrelevant historical reference points.

5. Overconfidence

Overconfidence is the tendency for individuals to overestimate their abilities, knowledge, or control over outcomes, often resulting in excessive risk-taking. In finance, overconfident investors may trade more frequently, underestimate risks, or overlook the benefits of diversification, believing they can “beat the market” with their skills alone. This behavior can lead to increased transaction costs and poor investment returns, as frequent trading rarely outperforms a well-diversified, long-term strategy. Being mindful of overconfidence encourages a more cautious and balanced approach to investing.

6. Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek out or interpret information in a way that confirms one’s pre-existing beliefs, while disregarding evidence that contradicts them. In finance, this can lead to one-sided decision-making. For instance, if an investor believes a certain stock will perform well, they may focus on positive news about the company while ignoring signs of potential trouble. Confirmation bias can result in risky investments and missed opportunities for diversification. Awareness of this bias encourages a more balanced evaluation of information, improving the likelihood of sound, evidence-based decisions.

7. Prospect Theory

Developed by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, prospect theory explains how people perceive gains and losses asymmetrically, often becoming risk-averse with gains and risk-seeking with losses. For example, investors may sell winning stocks too early to “lock in” profits but hold onto losing stocks, hoping they’ll recover. This behavior creates an inconsistency where investors make suboptimal choices, deviating from the rational expectation to maximize returns. Prospect theory underscores the importance of consistent decision-making and the need to resist emotional impulses when managing investments.

Some Biases Revealed by Behavioral Finance

Behavioral finance reveals various cognitive biases that often lead to irrational financial decisions, impacting both individual investors and broader market dynamics. These biases influence how people perceive and respond to risk, gains, and losses, often driving decisions that stray from rational analysis. Understanding these common biases can help investors become more aware of their own tendencies and make more informed financial choices. Here are some biases that behavioral finance brings to light:

1. Loss Aversion

Loss aversion is a powerful bias where the pain of losing feels significantly stronger than the pleasure of an equivalent gain. For example, losing $100 tends to feel worse than the satisfaction of gaining $100. In finance, this bias leads investors to avoid selling losing investments, as they don’t want to “lock in” the loss. Instead, they often wait, hoping the investment will recover, even if it may be wiser to reallocate to a stronger asset. Loss aversion can result in missed opportunities for growth and a reluctance to take calculated risks that could enhance long-term returns.

2. Overconfidence

Overconfidence is a bias where individuals overestimate their knowledge, expertise, or control over financial outcomes. This can lead to excessive trading, as overconfident investors believe they can “beat the market” through frequent transactions, despite evidence that passive, diversified strategies often perform better. Overconfidence also leads to risky investment choices and inadequate diversification, as investors rely too heavily on their own judgment rather than spreading risk across a balanced portfolio. This bias can be costly, as frequent trading and high-risk decisions often reduce overall returns.

3. Anchoring

Anchoring is the cognitive bias where people rely too heavily on an initial piece of information—or “anchor”—when making subsequent decisions. For instance, if an investor buys a stock at $50, they may become fixated on that price, viewing it as the stock’s “true value.” Even if the stock’s fundamentals have changed, the investor might hesitate to sell at $40, waiting for it to return to the anchor point of $50. This bias can lead to poor decision-making, as it causes individuals to ignore current market realities and stick to outdated reference points.

4. Herd Mentality

Herd mentality is the tendency to mimic the actions of a larger group, particularly in financial markets. When investors see others buying a particular stock or asset, they may join in to avoid missing out, often disregarding their own analysis. This can create unsustainable asset bubbles, as prices rise beyond actual value, or trigger market crashes when people panic-sell en masse. Herd mentality can lead to volatile markets driven by emotion rather than rational fundamentals, as investors blindly follow the crowd.

5. Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek out information that supports one’s existing beliefs while ignoring contradictory evidence. In finance, this bias can lead investors to overlook risks, as they only consider data that affirms their confidence in an investment. For example, an investor bullish on a stock might ignore indicators that suggest it’s overvalued, focusing instead on positive news. This selective perception often results in overcommitment to a single strategy or asset, making portfolios more vulnerable to market fluctuations.

6. Mental Accounting

Mental accounting is the habit of treating money differently based on its origin, purpose, or mental “category.” For instance, someone might be conservative with regular income but spend freely with a tax refund or bonus. This bias can affect investment decisions, leading people to take unnecessary risks or make inconsistent financial choices. For instance, keeping large amounts of money in low-interest savings while carrying high-interest debt reflects mental accounting, as people mentally separate funds rather than viewing their finances as a whole.

7. Familiarity Bias

Familiarity bias is the inclination to favor investments in familiar companies, sectors, or locations over unknown options. Many investors, for instance, prefer investing in domestic companies over international ones, regardless of potential benefits. While familiarity offers comfort, this bias limits diversification, as individuals may miss out on opportunities in unfamiliar sectors or markets. Familiarity bias can reduce a portfolio’s potential for growth and resilience, as it concentrates investments within a narrow field instead of spreading risk across diverse assets.

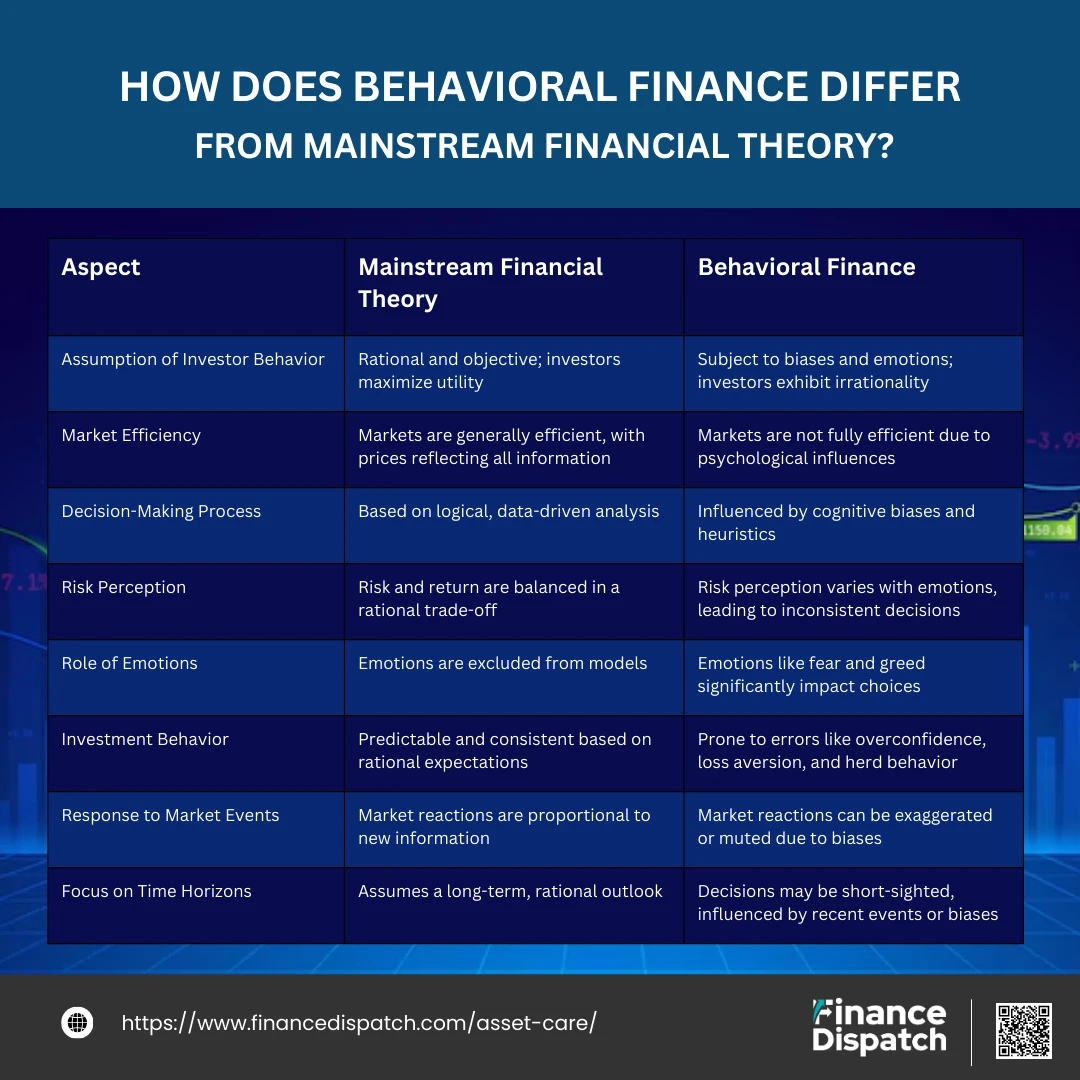

How Does Behavioral Finance Differ from Mainstream Financial Theory?

Here’s a comparison of key aspects between behavioral finance and mainstream financial theory:

| Aspect | Mainstream Financial Theory | Behavioral Finance |

| Assumption of Investor Behavior | Rational and objective; investors maximize utility | Subject to biases and emotions; investors exhibit irrationality |

| Market Efficiency | Markets are generally efficient, with prices reflecting all information | Markets are not fully efficient due to psychological influences |

| Decision-Making Process | Based on logical, data-driven analysis | Influenced by cognitive biases and heuristics |

| Risk Perception | Risk and return are balanced in a rational trade-off | Risk perception varies with emotions, leading to inconsistent decisions |

| Role of Emotions | Emotions are excluded from models | Emotions like fear and greed significantly impact choices |

| Investment Behavior | Predictable and consistent based on rational expectations | Prone to errors like overconfidence, loss aversion, and herd behavior |

| Response to Market Events | Market reactions are proportional to new information | Market reactions can be exaggerated or muted due to biases |

| Focus on Time Horizons | Assumes a long-term, rational outlook | Decisions may be short-sighted, influenced by recent events or biases |

Real-World Examples of Behavioral Finance

Behavioral finance provides valuable insights into real-world financial events, where investor psychology often leads to outcomes that defy traditional economic logic. These examples showcase how biases like herd mentality, overconfidence, and loss aversion manifest in financial markets, creating patterns, trends, and anomalies that shape investment strategies and market outcomes. Here are some notable real-world examples of behavioral finance in action:

1. The Dot-Com Bubble (Late 1990s)

During the dot-com bubble, herd behavior led to the overvaluation of technology stocks as investors poured money into internet companies, regardless of profitability or solid business models. This speculative frenzy was fueled by overconfidence and the fear of missing out, inflating stock prices to unsustainable levels until the bubble burst in 2000, leading to significant market losses.

2. The 2008 Financial Crisis

Loss aversion and overconfidence played a significant role in the 2008 financial crisis. Banks and investors continued to support risky mortgage-backed securities, assuming housing prices would only go up. When the housing market declined, loss aversion prevented early exit from deteriorating positions, while overconfidence in the financial system’s stability delayed corrective action, resulting in a global economic downturn.

3. GameStop Stock Surge (2021)

In early 2021, GameStop’s stock price surged as individual investors on online platforms, like Reddit’s WallStreetBets, collectively bought shares to drive up prices. This behavior was influenced by herd mentality, social proof, and a desire to counter large institutional investors, causing a massive, short-term price spike. The event showcased the power of coordinated action and the influence of social media on financial markets.

4. Cryptocurrency Volatility

The cryptocurrency market demonstrates behavioral biases like hyperbolic discounting, herd mentality, and overconfidence. Investors are often driven by the fear of missing out, leading to rapid price spikes and crashes in assets like Bitcoin. This volatility is exacerbated by a lack of intrinsic valuation metrics and the influence of emotions, making cryptocurrencies a prime example of behavioral finance dynamics.

5. Holding on to Losing Investments (Disposition Effect)

Many individual investors exhibit the disposition effect, where they hold on to losing stocks in hopes of recouping initial investments rather than selling at a loss. This behavior reflects loss aversion, as the emotional discomfort of realizing a loss outweighs the logic of reallocating to better-performing assets, leading to suboptimal portfolio performance.

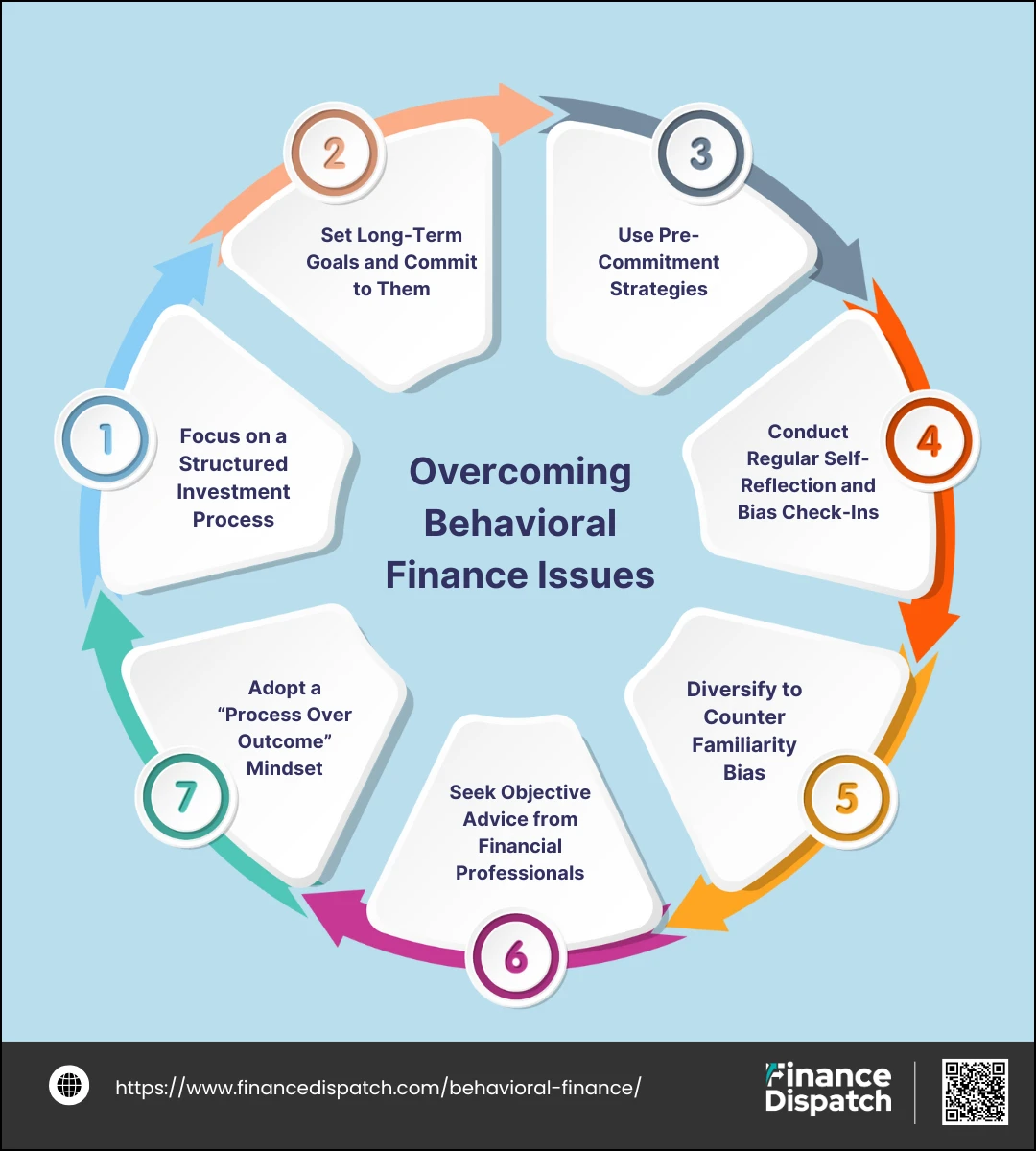

Overcoming Behavioral Finance Issues

Here are some effective ways to address and overcome behavioral finance issues:

1. Focus on a Structured Investment Process

A structured investment process involves setting specific guidelines and criteria for making investment decisions, such as asset allocation, risk tolerance, and diversification strategies. By following a clear, logical plan, investors are less likely to make impulsive decisions based on emotions or temporary market conditions. This approach creates consistency and discipline, helping to prevent biases like loss aversion and overconfidence from affecting portfolio choices. With a structured process in place, investors can navigate financial markets more objectively, focusing on long-term strategies rather than short-term emotional reactions.

2. Set Long-Term Goals and Commit to Them

Defining clear financial goals for the long term, such as retirement savings, property investment, or education funds, helps investors look beyond immediate market fluctuations. By anchoring their strategy to these long-term objectives, investors reduce the impact of biases like recency bias (where recent events overly influence decisions) or hyperbolic discounting (preference for short-term gains over larger long-term rewards). Committing to long-term goals encourages a steady investment approach, promoting a focus on sustainable growth rather than reactive, short-term moves.

3. Use Pre-Commitment Strategies

Pre-commitment strategies, such as automated contributions to savings accounts or regularly scheduled portfolio rebalancing, provide a practical way to counteract impulsive decision-making. These strategies take emotion out of the equation by enforcing predetermined actions, reducing the influence of biases like overconfidence (believing one can time the market) and loss aversion (reluctance to realize losses). By setting these “rules” in advance, investors can ensure consistency in their financial approach, even when market conditions are volatile.

4. Conduct Regular Self-Reflection and Bias Check-Ins

Self-reflection involves reviewing past financial decisions to recognize potential patterns of bias, such as confirmation bias (favoring information that supports existing beliefs) or anchoring (focusing too heavily on initial information). Regularly assessing these tendencies allows investors to identify and address personal biases, fostering self-awareness that can improve decision-making over time. Periodic “bias check-ins” serve as a reminder to approach each decision with fresh, objective analysis, promoting continuous improvement in financial strategies.

5. Diversify to Counter Familiarity Bias

Diversification, which involves investing across different asset classes, sectors, and regions, is a proven method to counteract familiarity bias—the preference for familiar investments like local companies or known industries. By diversifying, investors not only spread risk but also open themselves up to growth opportunities they might otherwise overlook. This approach reduces concentration risk and protects against market downturns in any single sector, encouraging a more balanced and less biased portfolio.

6. Seek Objective Advice from Financial Professionals

Consulting a financial advisor or an experienced mentor offers an objective viewpoint that can help investors make more informed decisions. Professionals can provide unbiased insights that counter personal biases, such as overconfidence (overestimating one’s expertise) or herd mentality (following others’ actions without independent analysis). By relying on expert guidance, investors can benefit from a more data-driven approach, reducing emotional influences and improving financial outcomes.

7. Adopt a “Process Over Outcome” Mindset

Emphasizing the decision-making process over the final outcome encourages a logical, methodical approach to investing. Instead of focusing on whether an investment was immediately profitable or not, investors are encouraged to evaluate whether their actions aligned with their overall strategy. This mindset helps reduce the emotional impact of wins or losses and minimizes biases such as regret aversion (avoiding action out of fear of future regret). Focusing on process reinforces the value of disciplined decision-making, leading to more consistent and rational choices.

Conclusion

In conclusion, behavioral finance offers invaluable insights into the psychological factors that shape financial decisions, often explaining why markets and individual investors deviate from the expectations of traditional financial theories. By understanding biases such as loss aversion, overconfidence, and herd mentality, financial professionals and individual investors alike can make more informed, balanced decisions that improve financial outcomes and reduce exposure to unnecessary risks. The practical applications of behavioral finance span personal financial planning, investment management, corporate strategy, and even public policy, providing a comprehensive framework to address irrational behaviors. Embracing behavioral finance not only leads to better decision-making but also fosters a deeper understanding of the complex, human-driven forces that influence financial markets. As the field continues to grow, its principles will likely become even more integral to developing strategies that promote financial well-being and stability across sectors.